Ecstasy

learning experiences inspired by the power of peak experiences

Awe. Rapture. Ecstasy. These mystical experiences feel transgressive in the school environment. They violate secular and even utilitarian bounds. To frazzled teachers seeking just a glimmer of engagement in a room full of sullen or pre-occupied adolescents, these words may fall on deaf ears. Yet, there are remarkable states of being accessible to the human mind that offer, there is no more profound word for it: “transcendence”. Preconceptions to the contrary, these states of mind are rich in meaning and utility. They have a legitimate place in school and it is time we reclaim them!

What if they knew? What if kids knew what their minds were capable of? What if they could enter a state of “Flow” at will, and strive for a state some call “Superfluidity”? What if they knew that rapture was real? I don’t mean a biblical “Rapture”, some kind of end-times scenario that works out badly for everyone but the chosen. Instead, imagine rapture with a lower case “r”, accessible without pharmaceuticals and without that inconvenient end-of-the-world thing. Imagine not Ecstasy the drug or that ecstasy of religious ritual, nor the ecstasy of extreme denial or starvation, but a mindset borne of flow—of mind and body in perfect unison. Perhaps that possibility is an incentive powerful enough to reclaim student engagement.

Reports of ecstasy come from the very extremes of athletic endeavor. The world-class ultra-marathon runner Chris Bergland writes: “Flow is to coitus as superfluidity is to orgasm” (Bergland, 2013, para. 6). That’s clearly not a scientific assessment, but it certainly captures the imagination. Whether it is a product of peak performance or oxygen deprivation, superfluidity deserves further investigation. Superfluidity I believe, is ecstasy.

The obstacle to ecstasy is utility. Schools demand productivity, and a mind in the thrall of ecstasy is neither rational nor productive. There is a whiff of disapproval about the very idea. Yet, it pains me to imagine that our schools would have students climbing the peaks of knowledge and deny them the thrall at the top. What is this ecstasy we are so suspicious of?

Ecstasy held as a religious phenomenon runs aground on what French philosopher George Bataille defined as the sacred: an intimacy that draws the subject “out of the world of utility and restores it to that of unintelligible caprice” (Bataille, 1989, p. 43). Schools focus on achieving the intelligible, not the unintelligible! Religious ecstasy is not what I am discussing here.

Ecstasy induced pharmaceutically is equally irrelevant. Drug-addled minds may be unproductive or unreceptive, though this is not necessarily so. This image of ecstasy stains our preconceptions, but this again is not the discussion here.

Ecstasy from sex is treated as a secret, at least in the United States. The journey is barred from all but the most mechanistic discussions, and the emotional outcome goes unacknowledged. This is sadly unproductive, but also not the concern here.

The ecstasy of interest here is the hard-won culmination of peak performance. It is the state of mind at the top of the mountain, the reward for maximum effort, the feeling achieved at the peak of flow. This ecstasy is not induced chemically, except by our innate chemistry. This ecstasy is not passively attained or irrationally induced. This ecstasy takes work! We should reclaim it, and reclaim lust as well: lust for adventure, lust for insights, lust for new experiences, and lust for life.

Bataille writes that humans seek in religion a lost intimacy, a connection to the world similar to the experience of animals in the wild. He describes this state as being like “water in water” (Bataille, 1989, p. 28), the most beautiful description of “oneness” I have ever read. This language is very similar to that employed by Chris Bergland when he describes Superfluidity as a state in which he feels completely at one with the world. Chris speaks of losing all self-awareness. Both Bergland and Bataille seem to describe a state of rapture that is accessible, but only with great effort.

Is it so difficult to imagine that our students, knowing rapture was possible and that school offered a path and a journey there, that they would look to their efforts with renewed anticipation, and engagement, and hope?

Question: How might you plot a path through your curriculum, culminating in rapture?

The postmodernists argue that Capitalism made identity its handmaiden, and when we make school about future employment, we forfeit the credibility to argue otherwise. If instead we focus school on developing all of our students’ faculties, rational and irrational, expressing and sensing, thinking and feeling, independent of any obvious utility, at that point do we wrest the narrative from the current, temporary needs of production and place it more firmly in the idealistic minds of the students themselves. We must expand, however, the menu of their future possibilities instead of focusing or curating it in the name of “excellence” or “productivity”.

That is the rub, isn’t it? Students need to believe in a safe, successful future as much as industry needs their labor. We are too quick to winnow anything “unproductive”, however, or too quick to let the students do it to themselves—STEM or STEAM the reductionist model du jour. We have made self-realization an indulgence, expression a hobby, and misalignments with the current needs of production a waste of time. “Exactly”, we say, proud of the efficient mill we have assembled. We are building students to be successful. That is the point of the exercise!

Unfortunately, cultural and technological shifts have achieved such speeds that the jobs of the future have become unimaginable. The trend to automated production and now machine intelligence already suggest a future without most of the jobs we know today, without obvious replacements offered. Productivity itself is stained with the ruin it has left in its wake: the devastated landscapes, the decimated wildlife, the disappearing ice caps, and the dirty air. Productivity is killing us.

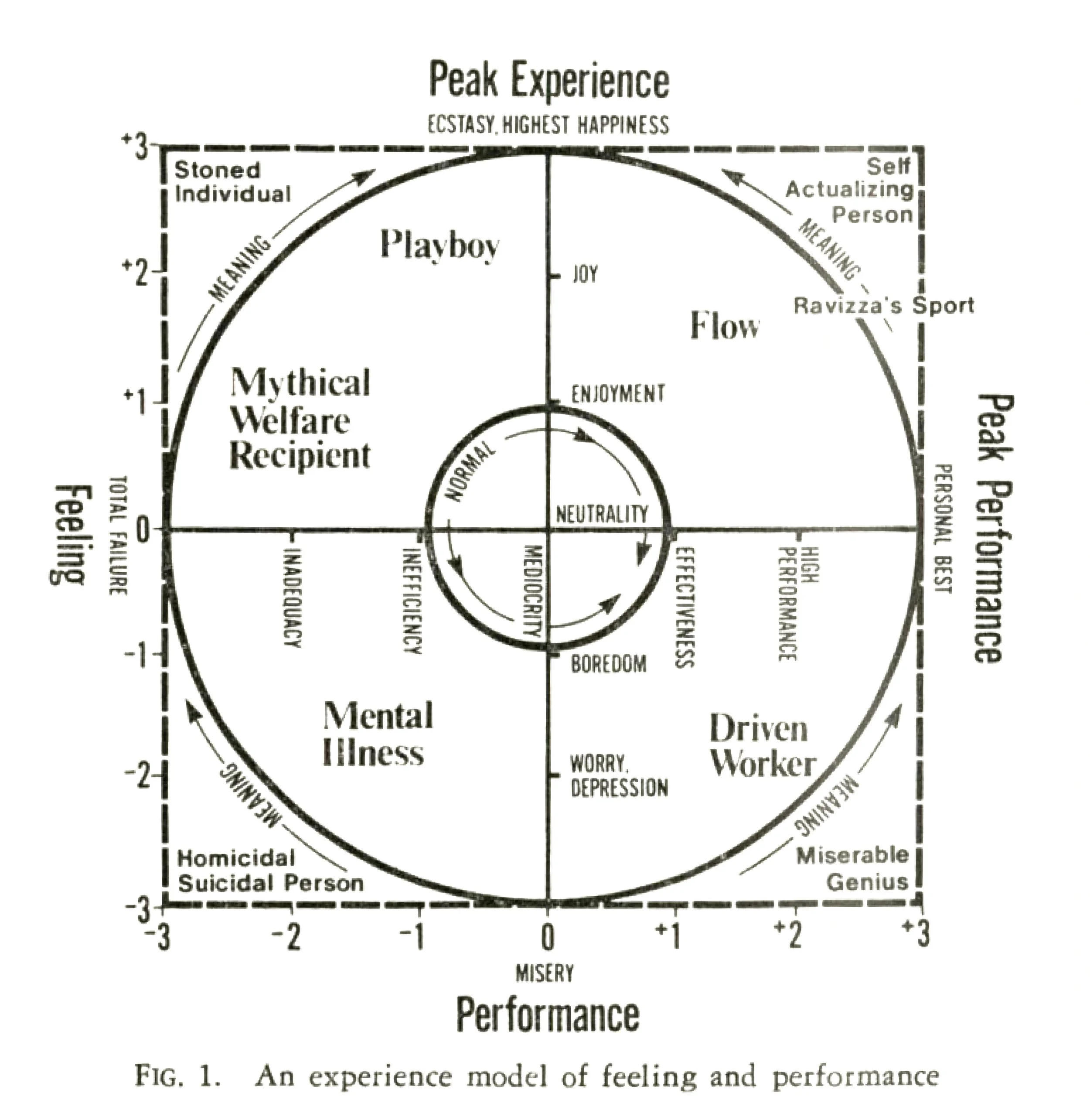

Culturally we will have to reinvent Capitalism. To contribute, school might keep students focused on developing all of their human capacities and not just those currently in demand. Thirty-five tears ago, Dr. Gayle Privette (1985) offered a useful perspective. He published this diagram to illustrate his idea to relate feeling and behavior in a Model of Experience:

Privette’s model illustrates beautifully the quotidian of experience. Dead center, it shows neutral feelings (“neutrality”) tied to uninspired performance (“mediocrity”). At the top left quadrant are all the pitfalls of ecstasy discussed earlier, the cheap and passive ecstasies of drugs and sex and religious rapture. The bottom right quadrant shows the efficient but uninspired cog-in-the-wheel, the effective drone, the soon-to-be-replaced-by-AI production worker, the focus I fear of so much education.

Only the top-right quadrant offers a satisfactory way forward. Self-actualization defines this quadrant, and it is here we find inspiration, meaning, joy and peak performance. Is this not what we hope for our children? Is this not exactly what is missing from the daily lives of too many of our students? Is this not what our schools should be modeling?

In focusing schools purely on cognition, do we not model the lower-right quadrant, requiring tremendous effort without the commensurate level of joy? Is it surprising that our children react by retreating to the upper left quadrant, to easy ecstasies that require no performance? Privette’s Model of Experience deftly illustrates the solution: we must strive for peak performance and peak experience together. Here we achieve ecstasy by reaching for our personal best, in the context of an amazing experience. Surely, the Puritans among us would not object?

“Life is not measured by the number of breaths we take, but by those moments that take our breath away. ”

Rapture and self-actualization-these are the rewards of refocusing our schools and our students on achieving peak experience and peak performance together. Still we might ask, “How do we do it”? We have a good understanding of “Flow”, of the need for immediate feedback and a careful balance between challenge and capability, between boredom and anxiety. What changes, however, a “job well-done” or a successful effort characterized by flow into ecstasy?

For a closer look at Ecstasy, I turned to Marghanita Laski’s work Ecstasy: a Study of Some Secular and Religious Experiences (1968). Laski was not a trained psychologist, but examined interview, literary and religious texts to identify the species of ecstasy and their triggers. “Intensity ecstasies” and “withdrawal ecstasies” received much of her attention, the former characterized by feelings of elevation, rhythm, satisfaction, enlargement, intensity, knowledge, unity, and renewal, the latter proffering a sense of floating, dissolving or melting.

For Laski, ecstasies move the abstract or intellectual into the realm of the emotional and even the mystical, citing Einstein who wrote:

“The most beautiful emotion we can experience is the mystical. It is the sower of all true art and science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger...is as good as dead. ”

Scientific work, poetic work, and creative work all have the potential to trigger ecstasy in Laski’s assessment. A “knowledge” ecstasy she describes as follows:

“It grants man a state of mind in which I believe he must come more and more to live: a mood of intensely conscious individuality which serves only to strengthen an intense consciousness of unity with all being. His mind is one infinitesimal node in the mind present throughout all being, just as his body shares in the unity of matter.”

Our schools as we know them now appear more preoccupied with distinctions than with unity, but even when they examine systems to emphasize unity, how often do they manifest a harmonious physical and emotional experience instead of a purely intellectual one?

Question: What do you do to create physical, emotional, intellectual learning experiences?

Triggers exhibit a range of qualities, writes Laski. Flow and rhythm figure powerfully in the texts she examined, as in music, in movement, and in experiences of water and the wind. Unification too is a prominent theme, as in solving a problem or achieving or discovering some harmony. When naturalist Gregory Bateson extols the “Pattern that Connects”, he intimates experience of this kind of ecstasy.

Amplification can trigger ecstasy, as when an experience enhances an incipient mood, and so too culmination, release, and renewal. Reaching the top of a tough climb, achieving your goal, relaxing your exertions and basking in just being: that is a profound species of rapture.

Laski cites specifically the transition from ignorance to inspiration or discovery as a trigger to ecstasy. The search for knowledge, for epiphanies, is a thirst for rapture! Moving the abstract into the emotional, this does align with the traditional mission of school. Laski reminds us that this is not something mysterious or magical, not something to be shunned or ignored as not worthy of the rational mind. Ecstasy is body, mind and spirit in harmony. Ecstasy is being “water in water”. Ecstasy is transcendence over self-doubt, self-awareness, anxiety and pain. It seems a worthy goal.

Question: How often do your lesson plans deliver these qualities?

Question: How often do you succeed in moving the abstract into the emotional?

That promise of ecstasy proves hollow however, at least for some.

I asked my daughter if she remembers even one instance of rapture in high school. The answer, predictably, was a quiet “no”. In fact, she felt the two worked diametrically in opposition. School actively slaughtered joy. The wearing competition and struggle with judgment by teachers and peers alike, the self-doubt and fear this engendered, the risk of failure and of public embarrassment all conspired to destroy what psychologist Erik Erikson called the moratorium needed for adolescent development. If my daughter’s experience is indicative, then high school is anti-ecstatic.

Question: Do you see transcendent joy in your wards?

Question: Is your school the site of ecstasy?

Laski compares intensity ecstasies with drug-induced ecstasies, noting that “Ecstatics are almost unanimous about the high value of their experiences. Mescaline users are not” (Laski, 1968, p. 269). Laski finds ecstatics rejoice in perfection, while mescaline users dwell on what is awry. Ecstatics never report the panic or terror drug users do. Without staking a moral position, Laski identifies the relative poverty of the drug-induced high.

Laski offers one of her most engaging ideas late in her book. “Ecstatic experiences are manifestations (probably exaggerated manifestations) of processes facilitating improved mental organization” (Laski, 1968, p. 280). This is a remarkable statement. Ecstasy in this view is a learning event: an optimizing experience. Laski likens it to conversion: “... a lasting and substantial mental reorganization, spontaneously achieved and accepted as beneficial” (p.280). It sounds eerily like religion. What intrigues me is that education might be poised, like religion, to offer a powerful and holistic world-view, albeit one constructed on a more refined set of evidence-based myths than the sort still reliant on ancient texts.

Conversion, revelation, inspiration: to Laski these are all mental reorganizations that differ only in the degree to which they rock your world. The lexicon of religion feels suddenly very comfortable in the context of education.

Still, you rationalists protest! The point of the scientific method is to banish belief. There can be no state of poise, no place for unquestioning acceptance. We seek grace in imbalance, the relentless “maybe”, and the endless “why”. Our “knowledge” is provisional, and so it will ever be. Do not speak of conversion lest our shoes land in dogma.

Our fear of calcification or rigidity cannot negate the power and potential of ecstasy however. Education does reorganize the mind. That finality eludes us does not preclude the dramatic possibility of conversion. After all, belief is not necessary to conversion, only change.

Here is the bottom line on ecstasy:

Our schools, in seeking to ignite engagement and develop every capacity of our students, must seek to maximize both peak experience and peak performance. Ecstasy is the pinnacle of both, and for that reason alone has a place in school. More importantly, ecstasy itself is a learning experience: a reorganization of the mind. It is also a benchmark, a touchstone, a reference point. It demonstrates to students not just what their minds are capable of, but also what life has to offer. In this sense, ecstasy offers hope and one answer to the existential question: “What is the point”? Experience, tool, possibility: these are all reasons to reclaim ecstasy for education.

References

Bergland, C.. (2011, October 29). Superfluidity: Peak performance beyond a state of ‘flow’. [Blog post on The Athlete’s Way]. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-athletes-way/201110/superfluidity-peak-performance-beyond-state-flow

Bataille, G. (1989). Theory of Religion. Zone.

Privette, G. (1985). Experience as a Component of Personality Theory. Psychological Reports. 56, 263-266

Laski, M. (1968). Ecstasy: In Secular and Religious Experiences. Greenwood.

Your thoughts on this journal post are highly valued, as I continue to build and refine my perspective on schools and the school environment. Please share your own experiences and perceptions of the school environment below!