Boredom

learning experiences inspired by…ugh

“Variety’s the very spice of life, That gives it all its flavour. We have run Through every change that fancy, at the loom Exhausted, has had genius to supply, And, studious of mutation still, discard A real elegance, a little used, For monstrous novelty and strange disguise.”

How is that for a boring quote to put you in the mood for this essay? If you are bored with teaching, or worry about being boring, or regularly confront students who say they are bored, what follows may be of some help to you. I will try not to bore you!

That opening quote comes from a book-long verse about a sofa—

and can’t seem to decide whether variety is spice or shallow caprice,

but gave us the cliché: “Variety is the spice of life”.

(Now you know).

Notice how the musty language in that quote tires you out before offering you any incentive at all to put up with it. Understanding it requires some tedious study. If you can cool your engines however, and settle your mind enough to concentrate on it, then you can appreciate that the tension between novelty and timeless elegance resonated 250 years ago, no less than it does today. Demanding extra energy from you before you are ready to commit that energy: that is a powerful invitation to boredom. It may offer you some insight into the experience of your students.

This got so long, it needs a Table of Contents:

1. Variety: in practice.

2. Variety: attracting attention.

3. Variety: risks.

4. Boredom: what is it?

5. Trait Boredom.

6. State Boredom.

7. Boredom: benefits.

8. Boredom: causes.

9. Conclusion

School can get tedious.

Can we agree on that? The teacher or the student may have had a bad day, or the student may be psychologically prone to boredom. The curriculum may be cumbersome to convey, or current events may have students’ minds elsewhere. The air conditioning might be out, or there may not be AC at all. Variety is the machete to hack through that jungle of smothering others: other things to do, other places to be, other people to see. Variety clears some space in your mind for engagement.

1. Variety: in practice.

Consider a teacher from my distant past in a place I won’t name. His teaching methods were . . . boring. Not just dull, but boring so as to sow utter despair. This teacher showed no emotions, shared no personal insights, inspired little interest, and drove that class quite literally to mayhem. Although our infractions proved egregious, and they embarrass me still, the reaction from this guy was . . . nothing at all. He just kept on talking . . . and talking . . . and talking.

I feel some empathy for that teacher; however, the lack of understanding and constructive communication in that classroom made it impossible to learn. By just talking, this teacher missed all kinds of opportunities to employ some variety to win our engagement.

He might have introduced contextual variety, either having us apply the lessons to different situations or taking us out of the classroom and teaching us somewhere else, perhaps outside.

He might have employed subject variety, teaching us about related subjects but having us use the knowledge and skills that he was actually trying to convey.

He might have employed pedagogic variety, employing different teaching styles to appeal to our many different styles of thinking and learning.

He might have employed emotional variety, by expressing his own feelings or by taking us for an emotional rollercoaster ride…although I guess he did, but it wasn’t aligned with anything he was teaching…

He might have employed physical variety to engage us in a range of activities besides listening and taking notes—anything to pump more blood and oxygen to the brain.

He might have employed variety to keep things unpredictable—to keep us literally on our toes.

He might simply have modulated his voice! None of this found a way into his repertoire, however.

Richard Feynman once wrote:

“My theory is that the best way to teach is to have no philosophy, [it] is to be chaotic and [to] confuse it in the sense that you use every possible way of doing it.”

Confusion!

Simultaneously introducing incompleteness and unpredictability, constantly re-contextualizing and occasionally obfuscating, turning learning into hide-and-seek and epic quests: it may sound a little chaotic, especially to a teacher focused on order, but it promises engagement.

2. Variety: attracting attention.

Variety is a powerful way to invite engagement. Change attracts our attention. Our systems monitor for it and our brain focuses on it, putting all else in the background. This also makes us extremely vulnerable to distraction. The fundamental mission and contribution of traditional education may actually be teaching us to control our focus even as we stay vigilant to changes in the environment. French philosopher Simone Weil expressed this succinctly decades ago:

“Although people seem to be unaware of it today, the development of the faculty of attention forms the real object and almost the sole interest of studies.”

“Self-directed neuroplasticity” is a fancy name for the idea that we shape our experience by developing our brains, in turn by controlling our attention. This has physical manifestations, since our brains develops in response to our use of it. The kicker is this, though: our brain does not just define how we “think”, it defines our very experience of life. By controlling our attention, we are refusing to allow circumstance to determine that experience. We are putting ourselves in the driver’s seat. Aldous Huxley captured this idea exactly when he wrote:

“Experience is not what happens to a man; it is what a man does with what happens to him.”

How is this for a vital lesson worth repeating as often as possible for the 12 or 16 years of a student’s attention: Learning all this stuff isn’t about the stuff, it’s about developing a mind designed to enjoy and make the most of life.

Consider perhaps:

Is this distinction between curriculum and purpose meaningful to you?

Do you ever give your students control over their attention?

Do your students understand the stakes?

Despite the immense personal power developed in controlling your attention, teaching often focuses on manipulating student attention (“classroom management”). It does not give students the awareness, motivation, strength, or tools to independently adjust their focus—to allocate this scarcest of resource, their time and attention. In our focus on conveying information within the time constraints of school, we must ask ourselves if we are failing to nurture independent minds. This is what professor of neuroethics and neurophilosophy Thomas Metzinger calls “mental autonomy”:

“What is clear by now is that our societies lack systematic and institutionalized ways of enhancing citizens’ mental autonomy. This is a neglected duty of care on the part of governments. There can be no politically mature citizens without a sufficient degree of mental autonomy, but society as a whole does not act to protect or increase it. Yet, it might be the most precious resource of all. In the end, and in the face of serious existential risks posed by environmental degradation and advanced capitalism, we must understand that citizens’ collective level of mental autonomy will be the decisive factor.”

Consider: How do you encourage your students to think for themselves?

Certainly, we have some say in defining our experience, but consider the forces we all face to understand how daunting it is to control our attention.

We grapple with trait factors, those characteristics that are baked into our very personality. We cannot resist the taboos we have learned, for example, and they inevitably distract our attention with irresistibly juicy stuff (MacKay et al., 2015). We can be plagued with anxiety and depression, and this loosens our control and brings pessimism to the fore (Berggren et al., 2013). Even our fear of spiders and snakes can heighten our expectation of negative outcomes (Muhlberger et al., 2006).

We also struggle with state factors, those characteristics that are more fluid or happenstance. These include physical deprivations like sleep (Higginson, 2017), food (Benton, 2010) and water (Khan et al, 2015). They may include mental deprivations like love and security (English, 2005). We grapple with moods that cause us to focus externally (happy) or internally (sad) (Sedikides, 1992), priming that keeps us focused on the last stimulus (Theeuwes et al., 2013), and our tendency to favor biologically relevant stimuli and anything about ourselves (Oliveira et al., 2013). We humans struggle with our limited cognitive load (how much we can focus on) (Lavie et al., 2004), and we struggle with competition (Sperber, 1996). Fending all this off to control our attention is no small feat.

Competition especially is what “persuasive technology” has foisted upon us (that’s all those apps on your phone, each one a siren on the rocks of distraction). As tech ethics expert James Williams articulates, persuasive technology is currently designed and operated to further its own agenda (drawing our attention), and not our own agenda (living an awesome life). What started as a tool to access and manage information has suddenly (literally, in the last 20 years) become our environment, which is to say that we no longer even fully realize the extent to which we have lost control of our attention, and thereby our will and our lives. We have become the tools of our tools.

“As digital technologies have made information abundant, our attention has become the scarce resource – and in the digital “attention economy,” technologies compete to capture and exploit our mere attention, rather than supporting the true goals we have for our lives. For too long, we’ve minimized the resulting harms as “distractions” or minor annoyances. Ultimately, however, they undermine the integrity of the human will at both individual and collective levels. Liberating human attention from the forces of intelligent persuasion may therefore be the defining moral and political task of the Information Age . . . The liberation of human attention may be the defining moral and political struggle of our time. ”

School minimizes sensory stimuli (competition) to manage or even manipulate attention: why else focus students on white boards in white boxes bathed in white noise? Sucking the spontaneity and stimuli out of school makes it easier to focus young minds on the curriculum.

While Indoctrination by Anaesthetization might “liberate human attention” from distractors, forcibly trading stimulation for understanding begins to feel like half a life and a false bargain as well. After all, this very book is premised on the idea that stimulation improves learning! Ideally, school aligns educational goals with enhanced stimulation that invites (students opt-in) rather than negotiates (students give up something) or coerces (students have no agency) for attention. (Williams, 2018)

““My experience is what I agree to attend to”.”

“My experience is what I agree to attend to” wrote psychologist William James back in 1890. What is this “agreement” though? Our brain is not just an instrument of thinking, it is also an instrument of feeling. The developing brain is not just about knowledge, but also about emotion and imagination and in fact our very experience of life. When I agree to attend to something, more often than not, it is because it makes me feel something. It makes me want something. It makes me hope something. It makes me fear something. It makes me care. This “agreement” is not some cold intellectual decision: it is raw and it is hot.

Consider this conundrum:

“The design of our brain’s attentional system suggests a curricular dilemma. The system evolved to quickly recognize and respond to sudden, dramatic changes that signal physical predatory danger, and to ignore or merely monitor the steady states, subtle differences, and gradual changes that don’t carry a sense of immediate alarm. However, schools must now prepare students for a world in which many serious dangers are subtle and gradual: overpopulation, pollution, global warming, acid rain, for example. How do we reset a powerful cognitive system to meet new challenges? ”

Thinking alone does not galvanize attention: it must be jolted with a charge of feeling. Hoping and fearing and caring—aren’t these the most powerful mechanisms by which we focus attention, in order to understand, in order then to love and hate, in order finally to lose ourselves in the world?

“For we, when we feel, evaporate.”

And are we not all seeking to find and finally open even a little, the doors to devotion? To care?

“Attention is the beginning of devotion”

Consider: How do you inject emotion into your curriculum?

3. Variety: risks.

What are the pitfalls of Variety?

Certainly if your focus is primarily on change, then it’s easier to fall victim to fashion. Someone else’s success with the latest methodology, someone else’s inspiring example, someone else’s idea of quality: you lose sight after a while of where you thought you were going. It helps to chart your course and invest in a responsive rudder instead of hoisting your sail and letting the wind determine your fate.

Variety also invites caprice: the siren song of the “new” luring you far from a focus on the “now” or the “good”. This is exactly what that opening quote from 1785 referenced, and I feel it in my own life. My craving for adventure and novelty argues powerfully for constant change, and only the counteracting desire for accomplishment, relationships, and love offers any balance.

The risk is that Variety leads you widely but not deeply, leaving you in the shallows. Width and depth both have their place, of course, but depth requires commitment, and that is a lot to ask of the young. Giving up on exploration and experimentation to focus on what is in front of you now feels a lot like “settling” when you could be and perhaps should be “seeking”. This issue is particularly poignant for families familiar with financial distress, who might wish their children to find safety in a good job as soon as possible rather than explore the world. That safety comes at the price of a nagging suspicion that something more enthralling may have lain just around the next bend. Miles down the road, when the bends have become boring, only then do we finally appreciate this proverb: No matter where you go, there you are.

4. Boredom: what is it?

If Variety is some kind of cure, what do we know of the disease? What about Monotony? What about Tedium? What about Boredom? Is there anything to be gained from them, or are they anathema to learning? Are we tasked to avoid Boredom at all cost, lest students shut down with all hopes for engagement lost? What is Boredom anyway, and is it good for anything? Could boredom be . . . interesting?

Psychoanalyst Otto Fenichel, writing just after World War II, called boredom a “tonically-bound cathexis”: a constant and unhealthy fixation. It is hard to shake off! It smothers you intellectually (I don’t know what will solve my problem), emotionally (I don’t believe anything will solve my problem), spiritually (I’m doomed: nothing will help me) and physically (my brain is insufficiently oxygenated and I feel sleepy, or I’m stuck waiting for a dentist appointment next to a pile of outdated magazines and can’t leave). Boredom is quicksand.

Dr. Stephan Vodanovich (1998) has been studying boredom for 30 years and defines it as “largely associated with a lack of external stimulation (perceived or real) and/or a lack of the cognitive skills to intrinsically generate interest” [italic emphasis mine], (p. 644). In other words, I could learn the cognitive skill of intrinsically generating interest to avoid boredom. I could teach or tame that voice in my head, pleading for freedom, adventure, surprise and awe, to be quiet.

Philosopher Andreas Elpidorou (2017, p. 2) approaches boredom as an emotion with five salient characteristics:

1. Affective (what it feels like): dissatisfaction or even frustration

2. Cognitive (effect on thought and perception): a perception of a lack of meaning

3. Physiological (effect on brain and body): attentional difficulty

4. Expressive (facial and bodily expression): disengagement with current situation

5. Behavioral/Motivational (actions, thoughts, desires prompted by the emotion): desire to escape it

The most satisfying definition for boredom, however, comes from Dr. John Eastwood from the University of York. He reconciles the many perspectives on Boredom by defining it in terms of Attention.

“Boredom is the aversive state that occurs when we (a) are not able to successfully engage attention with internal (e.g., thoughts or feelings) or external (e.g., environmental stimuli) information required for participating in satisfying activity, (b) are focused on the fact that we are not able to engage attention and participate in satisfying activity, and (c) attribute the cause of our aversive state to the environment.”

Boredom, in other words, warns us of a frustrating and dissatisfying emotional and intellectual disengagement. It is time to make a change!

Consider: Are your students empowered to “make a change” when they feel bored?

Boredom manifests as either a “trait”, in which boredom is pervasive and relentless, or a “state”, in which boredom is the response to immediate circumstances.

5. Trait Boredom.

As a trait (a characteristic firmly entrenched in your personality), boredom comes with a host of ills, from hostility to hopelessness, and anxiety to alienation. People who are easily and characteristically bored find self-actualization elusive (and self-actualized people tend not to get bored). This relationship suggests that a solution to one may well offer a path to solving the other. (Vodanovich et al., 1991)

Insofar as it impacts human flourishing, Trait Boredom, according to philosophy professor Andreas Elpidorou, could even been called a Moral Emotion:

“If the trait of boredom hinders elements of subjective, psychological, or social well-being, then trait boredom should be thought of as an obstacle to flourishing. It is precisely for this reason that trait boredom should be considered to be a morally relevant personality trait…Insofar as the trait of boredom opposes flourishing, self-growth, and well-being, it hampers a moral life.”

People short on absorption are prone to trait boredom: they are incapable of fully engaged attention and unable to stimulate themselves when external sources are inadequate. Because meditation teaches proficiency for absorption, researchers suggest that it may be an effective prescription for trait boredom. Negative self-awareness also correlates with trait boredom. Here therapy, journaling, and meditation have proven effective.(Vodanovich et al., 1998)

Consider perhaps:

How might you employ meditation to help your students grapple with boredom?

How might you encourage your students to journal?

How might you actively help them turn their journal daydreams into realities?

6. State Boredom.

State Boredom is our reaction to immediate circumstances. It is temporary, but as a teacher, it may be your worst nightmare. It sows doubt in your abilities. It unfairly separates classes into “good” kids (they’re docile or eager to please) and “bad” kids (they just can’t pay attention). It drives kids to counterproductive avoidance strategies: texting, checking out, smoking, fighting and risk-taking.

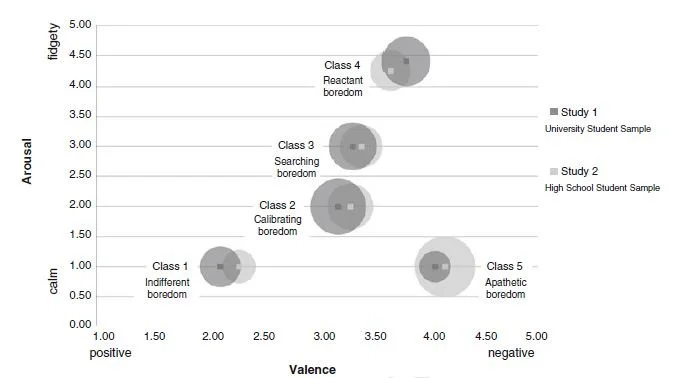

How bored do we get? Researchers grade Boredom on the degree to which it is a source of emotional arousal, with low arousal “indifferent boredom” (we’re not motivated to action) most typical of “non-achievement situations” like shopping and high arousal “reactant boredom” (we get angry and frustrated) most typical of “achievement situations” like classrooms. “Apathetic boredom” (we are beyond believing we can fix this) appears to be most unpleasant of all and is also more typical of “achievement situations” but is characterized by low arousal.

Types of Boredom: An experience sampling approach (Goetz et al., 2013)

Your students may be frogs in a pot you are slowly bringing to boil. Never sufficiently motivated or empowered to leap from the pot, they die of boredom. This is the graph of that experience: an insidious assault on the will, slowly sapping any ability to act, until finally all will is broken. If there is any hope of finding something positive in Boredom, it will lie in the lower classes of boredom where some will to re-engage remains. It is interesting to note that high school students display apathy far more than university students—a sign perhaps that they feel no sense of agency or have dutifully learned helplessness. Who taught them that?

Consider:

Is your classroom an achievement environment?

Or, is it perhaps something like a making, a curiosity, or a playful environment?

Do you struggle with apathetic students?

Could you be teaching them apathy?

Boredom can feel differently, depending on the situation in which you find yourself.

Savor some flavors of boredom:

Boredom: frustration from lack of interest

Merriam Webster: “the state of being weary and restless through lack of interest”

A desire for release from the tension induced by lack of stimulation in the absence of any drive to do anything about it.

Passivity and frustration as much as weariness

Restlessness: a dissatisfied frenzy triggered by boredom

Dictionary.com: “unquiet or uneasy, as a person, the mind, or the heart

Dictionary.com: “the inability to rest or relax as a result of anxiety or boredom”

Merriam Webster: “characterized by or manifesting unrest especially of mind”

Listlessness: a dissatisfied lack of energy triggered by boredom

Dictionary.com: “having or showing little or no interest in anything; languid; spiritless; indifferent”

Merriam Webster: “characterized by lack of interest, energy, or spirit, a melancholy attitude”

Rudderless, anchorless

Emptiness: a dissatisfied sense of meaninglessness

Vocabulary.com: “valueless, futile”

Dictionary.com: “without force, effect, or significance; hollow; meaningless”

The Abyss

Apathy: you care about nothing anymore

Merriam Webster: “lack of feeling or emotion, or lack of interest or concern”.

https://wikidiff.com: “complete lack of emotion or motivation”

A lack of Passion

Anomie: you’re adrift

Merriam Webster: “personal unrest, alienation, and uncertainty that comes from a lack of purpose or ideals”

Wikipedia: “"the condition in which society provides little moral guidance to individuals", “a dysfunctional ability to integrate within normative situations”.

Acedia: indifferent, no longer trying to be virtuous

Vocabulary.com: “apathy and inactivity in the practice of virtue (personified as one of the deadly sins)”

Dictionary.com: “laziness or indifference in religious matters, sloth”

Merriam Webster: “a lack of interest or caring, with overtones of laziness”

Ennui: weariness headed towards melancholia

Dictionary.com: “a feeling of utter weariness and discontent resulting from satiety or lack of interest”

https://wikidiff.com: “the difference between boredom and ennui is that boredom is the state of being bored while ennui is a gripping listlessness or melancholia caused by boredom; depression”

Melancholia: all is lost

Vocabulary.com: “a state of deep sadness”

Dictionary.com: “a mental condition characterized by great depression of spirits and gloomy forebodings”

Merriam Webster: “severe depression characterized especially by profound sadness and despair”

Anhedonia: inability to feel pleasure

Ugh!

Language allows us to distinguish between two different kinds of boring experiences. Consider:

Tedium: too long or too slow

Dictionary.com: “the quality or state of being wearisome”

Vocabulary.com: “dullness owing to length or slowness”

Merriam Webster: “Latin taedium disgust, irksomeness, from taedēre to disgust, weary”

Monotony: too repetitive or the same

Dictionary.com: “wearisome uniformity or lack of variety”

Vocabulary.com: “the quality of wearisome constancy, routine, and lack of variety”

Merriam Webster: “tedious sameness”

7. Boredom: benefits

What good is Trait Boredom? What good is State Boredom? In fact, both can come with positive outcomes. It is useful to consider how school might take advantage of this potential, or how it frustrates those potential benefits.

Trait Boredom

Jennifer A. Hunter in her thesis, The Inspiration of Boredom: An Investigation of the Relationship between Boredom and Creativity (2015), found that: “Trait boredom, controlling for overall personality structure, was a positive predictor of curiosity…, and curiosity in turn was found to be a positive predictor of creative performance” (Hunter, 2015, Abstract).

If Curiosity burns among the coals of Trait Boredom, we might ask at school: what is feeding the flames? Does your environment offer the twigs and tinder to bolster the burn: problems and possibilities to feed that curiosity? Does your culture even offer students the time and agency to build a fire?

“The cure for boredom is curiosity. There is no cure for curiosity.”

Consider: How can you adjust the activities of those students who chronically express boredom, to take maximum advantage of their strong curiosity and creativity?

State Boredom

State Boredom, too, has its upsides. If it does not inspire indifference, inaction, or an emotional outburst, state boredom can yield positive results:

1. Boredom spurs creativity and greater self-reflection. In an article in Research in Middle Level Education, researcher James D. Williams describes a study in which junior high school students who were denied electronic diversions either quit the study in frustration or developed tools of self-reflection. The pay-off for hanging in there was found in improved academic performance and improved self-esteem. (Williams, 2006)

Consider:

If Boredom promotes self-reflection (a pre-requisite to self-actualization: know thyself) but risks emotional repudiation (two of the three subjects quit), how do you manage it or take advantage of it?

Is there unprogrammed time in your student’s day, for example, to encourage reflection or meditation? If so, then what?

Is there an opportunity to interrogate the introspection and examine the implications—to turn thinking into a plan of action?

Should school not be a protagonist in nurturing thoughts into realities?

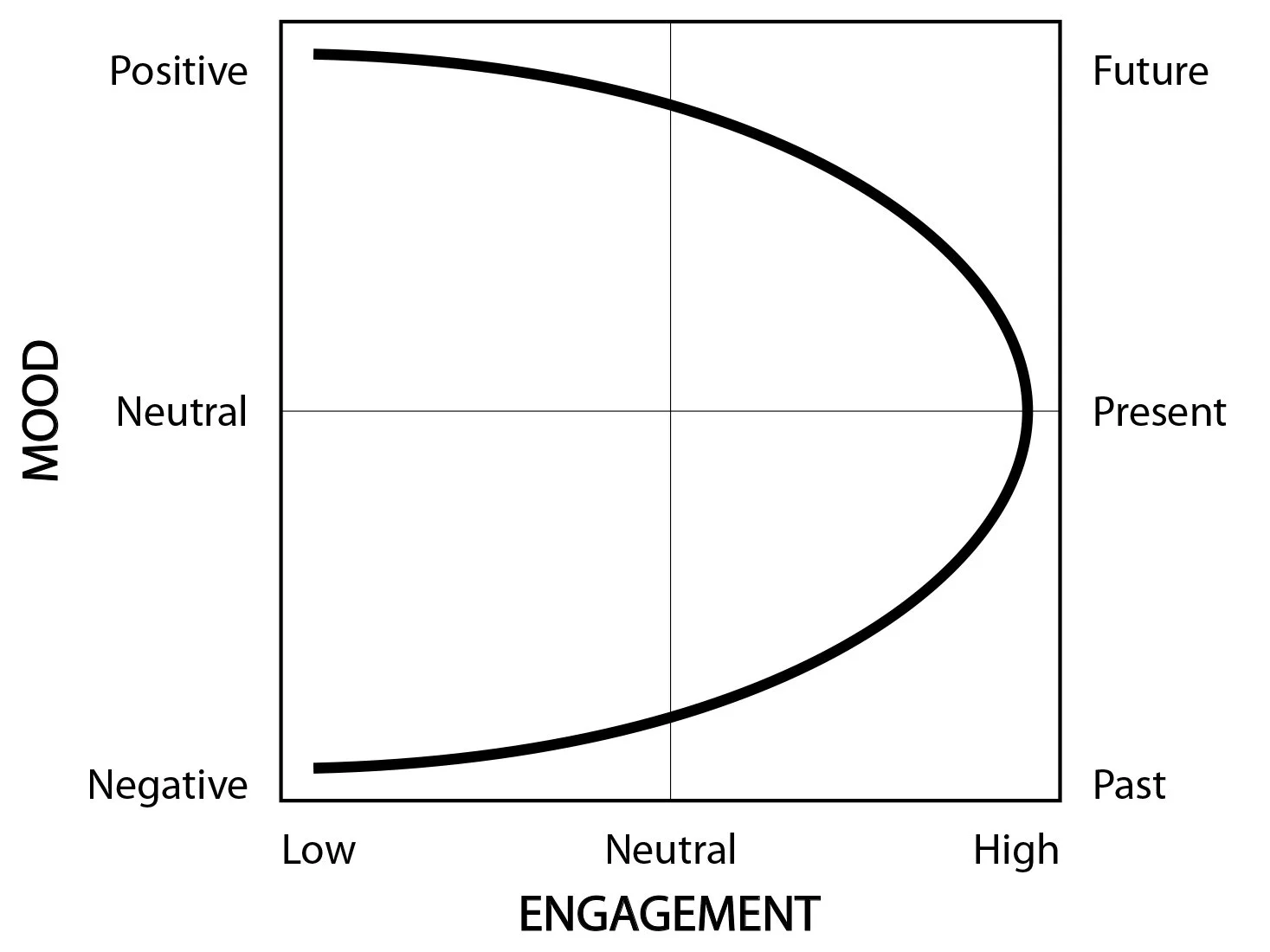

2. Boredom coupled with the opportunity for mind-wandering focuses us on ourselves. It also focuses us on the future, enhancing goal-orientation, at least when the subject is in a neutral or positive mood. It makes planners out of us, and can be especially useful when we focus on obstacles and not just outcomes. A negative mood focuses us more on the past and is less productive. The key is having more working memory available than the current task requires—in other words, being under-challenged or bored. (Mann et al., 2014)

Stimulating engagement, in other words, is a teaching tool. Limit it productively to encourage self-knowledge and future plans, and develop strategies for capturing the ideas that emerge from mind-wandering. Alternatively, increase variety, social engagement, challenge, and student agency to focus students on the lesson at hand. While not the least bit scientific, we might hold it as follows:

Consider:

Do you accept the utility of mind-wandering in a school setting?

How might you orchestrate the ebb and flow of energy and engagement in your classroom?

3. Boredom increases and improves creativity. When researchers Sandi Mann and Rebekah Cadman gave study participants a test for lateral thinking, or a variety of boring tasks before that test, students who were bored in advance proved more creative, generating more and better ideas on the lateral thinking test. Bored people think more creatively than those who are not. An interesting hypothesis proposed by the study is that daydreaming inspired by the boring task was the mechanism inspiring creativity afterwards. Boring tasks that prevented daydreaming (boring writing) yielded less creativity than boring tasks that promoted daydreaming (boring reading). Daydreaming unlocks creativity. (Mann et al., 2014)

If Boredom plants the seed of Creativity, what nourishment do you offer the seedling? Do you offer the time for daydreams? Afterwards, does your environment offer the tools, the raw materials, and the culture for creating/experimenting/tinkering?

Consider: Creativity Desert or Creativity Oasis, what are you?

4. Professor Elpidorou extols boredom for its regulatory function:

“Boredom (in its non-pathological, state form) is valuable to us precisely because its presence helps us to keep moving and in doing so, it brings us closer to what is in line with our desires and goals. It is not news to state that there is a place for negative emotions and affective states in our well-being…It is news, however, to propose that boredom can be an element of the good life. ”

If Boredom plays an important regulatory function, if it helps us to adjust our circumstances to recapture a lost state of “flow,” for example, does school offer students the agency to adjust their activity, environment, or intention in response? Or does it enforce passivity in the face of alarm bells? Research shows student agency decreases with age in the traditional classroom setting, which is the opposite of their developmental needs. (Eccles et al., 1993)

Consider: If Boredom says it’s time to jump into action before it puts you to sleep but your rules demand the opposite, have you not taught helplessness instead of empowerment?

5. Boredom makes us more altruistic. We are meaning-seeking creatures, and when boredom strikes, it does so with a sense of meaninglessness. Altruism is one way we regain a sense of meaning. Wijnand Van Tilburg in his doctoral research found the following:

“Consistent with our prediction, participants were willing to donate more to charity under high compared to low boredom. Given that charity support as a specific form of prosocial behavior increases when experiencing a threat to one’s perceived meaningfulness, and that prosocial behavior has been generally related to attainment of a sense of meaningfulness…these results support the hypothesis that people who are bored engage in responses that have the potential to re-establish a sense of meaningfulness.”

This study found that people prefer to seek meaning in activities aligned with their goal pursuit over activities that do not, and that they do not act out of a desire to simply feel good: they will choose meaningful activities even if they might result in unpleasantness.

We exhort students to appreciate acts of service, but am I alone in wondering if they do so out of a sense of obligation or a desire for credit or approval? After a boring activity — that is the moment for students to find personal meaning in altruistic acts.

We might heed the results of Thomas Goetz’s research, however, in which he found that the setting as well as the type of boredom played a role in positive outcomes, and that a positive outcome is never certain:

“With respect to the possible positive aspects of boredom experiences…it may be assumed that different types of boredom can differ with respect to their potential to initiate positive thoughts and actions. For instance, indifferent boredom experienced mainly in non-achievement settings may be related to constructive behaviors such as stimulating greater self-reflection and creativity… At the same time, the potential benefits of boredom in more restrictive achievement situations [think traditional classrooms] may be more limited. Further, our studies revealed that indifferent boredom was the least commonly experienced boredom type

(16 % in university students, 11 % in high school students). Hence, the potential benefits associated with this type of boredom are likely to be outnumbered by the negative consequences of more aversive boredom types. ”

Let’s not imagine Boredom, in other words, as a key to the kingdom of creativity or self-actualization. Let’s not forget that self-actualization emerges at the intersection of Peak Performance and Peak Experience, a space with too much oxygen to support Boredom.

Faced with Boredom as a practical issue, however, you might ask if your classroom is an “achievement” or “non-achievement” setting. Faced with a bored student, you might ask if there is an option to move them into a non-achievement setting that might stimulate self-reflection and creativity.

Consider:

Is sending a bored and disruptive student to the office merely a way to avoid the responsibility you had to meet them where they are, and a failure to use their emotional state to teach them how to work it to their advantage?

Why not give them some time without expectation of achievement, in a workshop surrounded by tools, materials, and references, for example, to exercise curiosity and creativity?

Zen Buddhism suggests we simply accept Boredom as a threshold to tranquility and a door to liberation.

“One point of all this of course is that as we learn to meditate we are learning what it’s actually like to be at peace. And since we tend to be so utterly revved up, peace and ease can feel deadly boring at first. So we have to move through this realm of generally unwanted and unappreciated feelings–an emotional geography we typically label as boring– as we acclimatize to contentment and peace.”

Instead of a signal to regulate or readjust, Boredom to Zen is merely a phase that will pass. As you reconnect to intuition and re-align action with purpose through meditation, your body and mind adjust to less stimuli. Boredom is that adjustment: a decluttering of thought and action that ultimately yields peace of mind. In that sense, Boredom can be considered a strategy. As unbearably difficult as I find it to stay awake through that process at times (glasses of ice water help immensely), the reward is always clarity and energy. That is an interesting lesson for a youngster for whom Boredom and its discomforts feel like a bottomless abyss.

Consider:

Will the time you offer your students for meditation be repaid in clarity, energy, and engagement?

Will you ever know if you don’t try?

8. Boredom: causes.

Tedium (circumstances that move too slowly or take too long) and Monotony (circumstances that are too predictable or repetitious) are the obvious answer, but it’s the wrong question. We might ask instead: “What is it within ourselves that causes us to feel bored”? Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of optimal experience (“flow” experiences) suggests that we all have a psychological requirement to balance ability and challenge: that when a situation is too challenging, we feel anxious, and when it is insufficiently challenging, we feel bored. Flow is described by Csikszentmihalyi as “autotelic”, meaning that it is intrinsically motivating and meaningful. In other words, the condition of flow itself is rewarding, no matter the task or context involved.

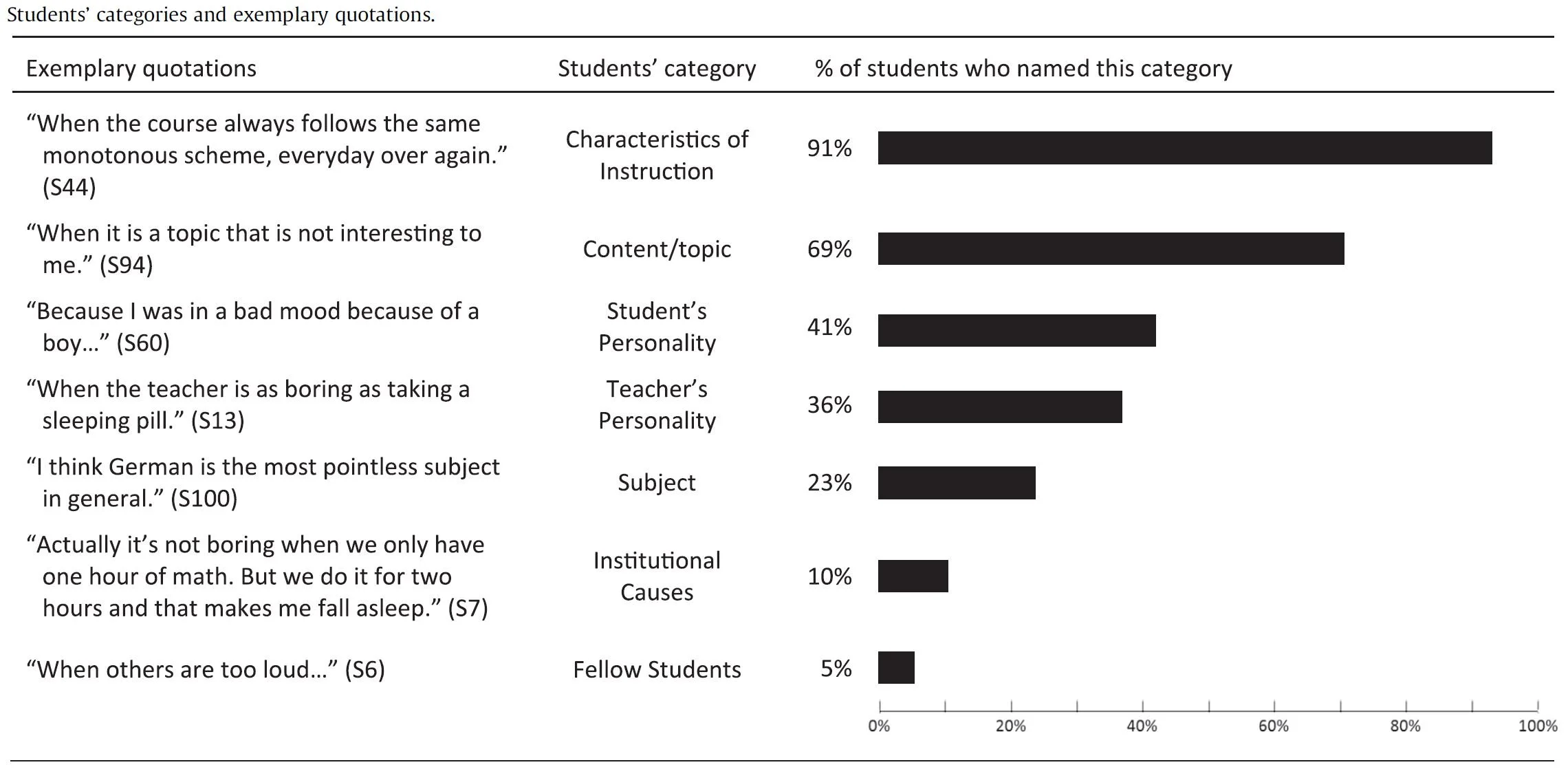

Researchers in Germany (Daschmann, 2014, pp. 22-30) interviewed 111 ninth graders and their teachers to better understand what bored students in school. The results speak for themselves:

The study discovered that teachers and students largely agree on what bores students (although teachers were reticent to identify themselves as a potential source), but goes no further to explore why teachers are unable to more successfully avoid boring students. Certainly, it is a masterful feat to be relevant, interesting, concise, and also bring 25-30 disparate students to a constant state of flow. Either the students must be filtered and grouped to operate in the same way (hence those “gifted” and “honors” programs), or they must be so starved of stimulation that they act in unison to embrace it, or they must be given the agency to self-adjust their activities and their circumstances. Segregate, starve, or empower: you choose.

Consider:

Do your students have the agency and maneuvering room to find and maintain flow: to improvise?

Is that not easier than trying to conduct the entire symphony on your own?

9. Conclusion

What good is your knowledge, teacher, if it doesn’t agitate, incite, or inspire me to feel? If it doesn’t provoke? Your sealed and stripped down classrooms, your abstract concepts and conversations, your plans for my future: can you understand that they don’t feed this physical ache for visceral engagement, challenge, and risk? I want to feel devotion, but just as often wind up feeling restless. Commitment is a gamble, often enough paid out in boredom. Do we all wrestle with these tensions, between capability and desire, between patience and urgency, between beginner’s mind and making a difference, between learning and doing? I want to feel oceans choking on plastic, sea life desperate for oxygen, bees ulcerating on chemicals, and soils bleeding methane. I want to feel the hunger, pain and desperation of the dispossessed, just as I want to smell the balsam wind of the Himalayas, spit Saharan sand out of my teeth, and soak in a rainy season in the Amazon. If you must confine me to your airless schools and demand of me my time and attention, and see that I demand of myself some elusive peak performance, repay me at least with moments of awe and surprise and joy. Repay me in peak experiences, not bleak approximations.

When lessons get abstract, as inevitably they must, remember that Variety is useful, (sparking engagement with gaps and changes, deepening understanding through re-contextualization and improving memory by increasing dose). Remember as well that Boredom also has its uses (promoting curiosity, creativity and self-reflection). If you want me to learn something, Variety increases retention and depth. If you want me to imagine or produce something, Boredom primes me for creativity.

Teachers (and Students): choose your weapon well.

References

Baird, B., Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. (2011, December). Back to the future: Autobiographical planning and the functionality of mind-wandering. Consciousness and Cognition, 20(4) pp.1604-1611

Benton, D. (2010). The influence of dietary status on the cognitive performance of children. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 54, 457–470 DOI 10.1002/mnfr.200900158

“7-year olds had an increased ability to sustain attention and were less likely to become frustrated after a glucose drink…The ability to sustain attention was better an hour after eating breakfast in boys aged 9–12 years, although memory was unaffected.”

Berggren, N., Richards, A., Taylor, J. & Derakshan, N. (2013, May 13). Affective attention under cognitive load: reduced emotional biases but emergent anxiety-related costs to inhibitory control. Front. Hum. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00188

Anxiety and depression leave us psychologically at-risk and less able to manage our own attention, though we may at least appreciate that emotional stimuli lose their power when we have a lot on our minds.

Cowper, W. (1785, June). The task.

Daschmann, E. C. (2014). Exploring the antecedents of boredom: Do teachers know why students are bored? Teaching and Teacher Education 39 pp.22-30, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.11.009

Eastwood, J. D., Frischen, A., Fenske, M. J. & Smilek, D. (2012, September 5) The Unengaged Mind: Defining Boredom in Terms of Attention. Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., Midgley, C., Reuman, D., Mac Iver, D. & Feldlaufer, H. (1993, May). Special Issue: Middle Grades Research and Reform. The Elementary School Journal, 93(5), pp.553-574

Elpidorou, A. (2017, March 1). The Moral Dimensions of Boredom: A Call for Research. Review of General Psychology. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1037/gpr0000098

Elpidorou, A. (2018). The Good of Boredom. Philosophical Psychology, 31:3, 323-351. DOI: 10.1080/09515089.2017.1346240

English, D. J., Thompson, R., Graham, J. C. & Briggs, E. C. (2005, May). Toward a Definition of Neglect in Young Children. Child Maltreatment, 10(2), 190-206. DOI: 10.1177/1077559505275178

“Specifically, verbally aggressive discipline is significantly associated with caregiver reports of both externalizing and internalizing behaviors, including reports that the child is anxious/depressed, has attention problems, exhibits delinquent and aggressive behaviors and has somatic complaints”.

Feynman, R. P. (1999). The Pleasure in Finding Things Out. Helix.

Fromme, E. (1942). The Fear of Freedom. http://www.yorku.ca/dcarveth/erich-fromm-the-fear-of-freedom-escape-from-freedom-29wevxr.pdf

Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Hall, N. C., Nett, U. Pekrun, R. & Lipnevich, A. (2013, November). Types of boredom: An experience sampling approach. Motivation and Emotion. DOI: 10.1007/s11031-013-9385-y

Higginson, J. (2017, September 14). Struggling to pay attention? Lack of sleep may be to blame. Alaska Sleep Clinic. https://www.alaskasleep.com/blog/struggling-to-pay-attention-lack-of-sleep-may-be-to-blame

“During an fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging)…[an] individual who is sleep deprived will show reduced metabolism and blood flow to multiple areas of the brain. These reductions in metabolism and blood flow have been linked to difficulty focusing, forgetfulness, lack of concentration, problem paying attention, short attention span, irritability, lack of impulse control, mood swings, depression, learning difficulties, and risky behavior”.

Hunter, J. A. (2015, June). The Inspiration Of Boredom: An Investigation of the Relationship Between Boredom and Creativity. York University, Toronto, Ontario

Huxley, A. (1959). Texts and Pretexts. Chatto & Windus. London.

James, W. A. (1890/1950). The Principles of Psychology. Dover. p402

Jarow, O. (2018, April 10). Attention, Autonomy, & the Hijacking of Evolution: A Culture of Consciousness. Musing Minds. https://musingmind.org/essays/attention-autonomy

Khan, N.A., Raine, L. B., Drolette, E. S., Scudder, M. R., Cohen, N. J., Kramer, A. F. & Hillman, C. H. (2015) The Relationship between Total Water Intake and Cognitive Control among Prepubertal Children. Ann Nutr Metab 66 (suppl 3) 38–41, DOI: 10.1159/000381245

“…higher water intake correlated with greater ability to maintain task performance when inhibitory demands are increased”

Lanham, R. A. (2001, January 15). Barbie and the Teacher of Righteousness: Two Lessons in the Economics of Attention, Houston Law Review (38), Conversations About The Law Cutting Continuity–Show #27

“So, what is scarce? Not information but the human attention needed to make sense of it. We are really living in an economics of attention, not an economics of information”.

Lavie, N., Hirst, A., de Fockert, J. W. & Viding, E. (2004, October). Load Theory of Selective Attention and Cognitive Control, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133(3), 339–354.

Studies suggest that when we have a lot of perceptual stimulus (I’m sitting in a café), we are able to ignore perceptual distractions (it’s my favorite and most productive environment to study and write), but when we have a lot on our minds (high demand on memory especially), we find it very difficult to actively filter out distractions.

“selective attention involves two dissociable mechanisms of control against distractor intrusions: a perceptual selection mechanism that reduces distractor perception in situations of high perceptual load and a cognitive control mechanism that acts to ensure that attention is allocated in accordance with current stimulus-processing priorities and thus minimizes intrusions of irrelevant distractors as long as working memory is available to actively maintain the current priority set (in situations of low working memory load)”.

MacKay, D. G., Johnson, L. W., Graham, E. R. & Burke, D. M. (2015). Aging, Emotion, Attention and Binding in the Taboo Stroop Task: Data and Theories. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 12803-12833. doi:10.3390/ijerph121012803

Research confirms that taboos get us emotionally charged, easily attract our attention and improve our memory of related events. (Yes, taboos are a potentially potent teaching tool).

Mann, S. & Cadman, R. (2014). Does being bored make us more creative”? Creativity Research Journal, 26 (2). ISSN 10400419. 165-173.

Metzinger, T. (2018, January 22). Are you sleepwalking now? Aeon Magazine.

Mühlberger, A., Wiedemann, G., Herrmann, M. & Pauli, P. (2006). Phylo- and Ontogenetic Fears and the Expectation of Danger: Differences Between Spider- and Flight-Phobic Subjects in Cognitive and Physiological Responses to Disorder-Specific Stimuli. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(3) 580–589.

Fears you are born with are typically more powerful attention dominators than fears you learn through experience. Even more interesting: these stimuli affect your beliefs about unrelated circumstances. You begin to expect things will go badly.

Nelson, M. (2018, September 22). The virtues of boredom. Sweeping Heart Zen. https://www.sweepingheartzen.org/the-virtues-of-boredom/

Oliveira, L., Mocaiber, I., David, I. A., Smith Erthal, F., Volchan, E. & Garcia Pereira, M. (2013, July 12). Emotion and attention interaction: a trade-off between stimuli relevance, motivation and individual differences. Front. Hum. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00364

Anxious people react faster to fear-related stimuli, and everyone reacts faster to biologically relevant imagery and materials related to themselves.

“… the relevance of a stimulus determines its subsequent attention allocation. Interestingly, these findings also suggested that stimulus relevance may be enhanced if the stimulus is personally meaningful. Thus, stimuli processing is prioritized and might recruit additional resources even in situations where visual information attentional resources are very limited”.

Sedikides, C. (1992) Mood as a Determinant of Attentional Focus”, Cognition and Emotion, 6 (2), 143.

Our degree of happiness changes what we pay attention to.

“Sad mood (in comparison to neutral and happy moods) tends to elicit self-focused attention, and happy mood (in comparison to sad mood) tends to invoke external-focused attention”.

Sperber, Dan et al, (1996). Relevance, Communication and Cognition, Blackwell, Cambridge. p292

We are guppies in a game of attraction, swimming in a sea of stimuli. Those stimuli all presume relevance and require our processing, if only to reject them as currently irrelevant to us. It is hard to stay “on-topic”.

“…every act of ostensive communication creates a presumption of relevance”.

Sylvester, R. & Cho, J.-Y. (1992) What brain research says about paying attention. Educational Leadership, 50(4). http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/dec92/vol50/num04/What-Brain-Research-Says-About-Paying-Attention.aspx

Theeuwes, J. & Van der Burg, E. (2013). Priming makes a stimulus more salient. Journal of Vision, 13(3):21, 1–11. http://www.journalofvision.org/content/13/3/21

Our brains automatically favor new stimuli that share characteristics of prior stimuli.

“the mere processing of [a] stimulus feature (even when it is completely irrelevant) renders that stimulus feature more salient”.

Van Tilburg, W.A.P. (2011). Boredom and its Psychological Consequences: A Meaning-Regulation Approach [PhD Thesis], University of Limerick, Ireland

Vodanovich, S. & McLeod, C. (1991, January). The relationship between self-actualization and boredom proneness. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality 6(5), 137-146

Vodanovich, S. & Seib, H. (1998). Cognitive Correlates of Boredom Proneness: The Role of Private Self-Consciousness and Absorption. The Journal of Psychology, 132 (6)

Weil, S. (1951) Waiting for God. [E. Craufurd, Trans.] Harper & Row.

Williams, J. D. (2006). Why Kids Need To Be Bored: A Case Study of Self-Reflection and Academic Performance, RMLE Online, 29(5)

Williams, J. (2018). Stand Out of Our Light, Freedom and Resistance in the Attention Economy. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/3F8D7BA2C0FE3A7126A4D9B73A89415D/9781108429092AR.pdf/Stand_out_of_our_Light.pdf?event-type=FTLA

James Williams believes we need to be more precise about the language of persuasion, linking the agency of the subject (Degree of Constraint) to the level of Goal Alignment between subject and tool (or subject and teacher by analogy). He offers the following framework, as useful to teaching strategy as it is to effective technology.

I will leave you with one final thought:

“To be “emotional” has become synonymous with being unsound or unbalanced. By the acceptance of this standard the individual has become greatly weakened; his thinking is impoverished and flattened. On the other hand, since emotions cannot be completely killed, they must have their existence totally apart from the intellectual side of the personality; the result is the cheap and insincere sentimentality with which movies and popular songs feed millions of emotion-starved customers.”

Your thoughts on this journal post are highly valued, as I continue to build and refine my perspective on schools and the school environment. Please share your own experiences and perceptions of the school environment below!